The shirt read: “Proud member of the Forget Your Feelings Generation.”

That was the display on the back of the T-shirt of the middle-aged man in the last row. Only, the first word wasn’t actually “forget,” though it did start with F. He was listening to speakers instructing him how to “go to the mind gym” and to “open your mind, open your heart.” From his look, the membership to the FYF Generation hadn’t included many passes to “the mind gym” over the years. And any opening of his heart at a forum surrounded by dozens of strangers might require the Jaws of Life.

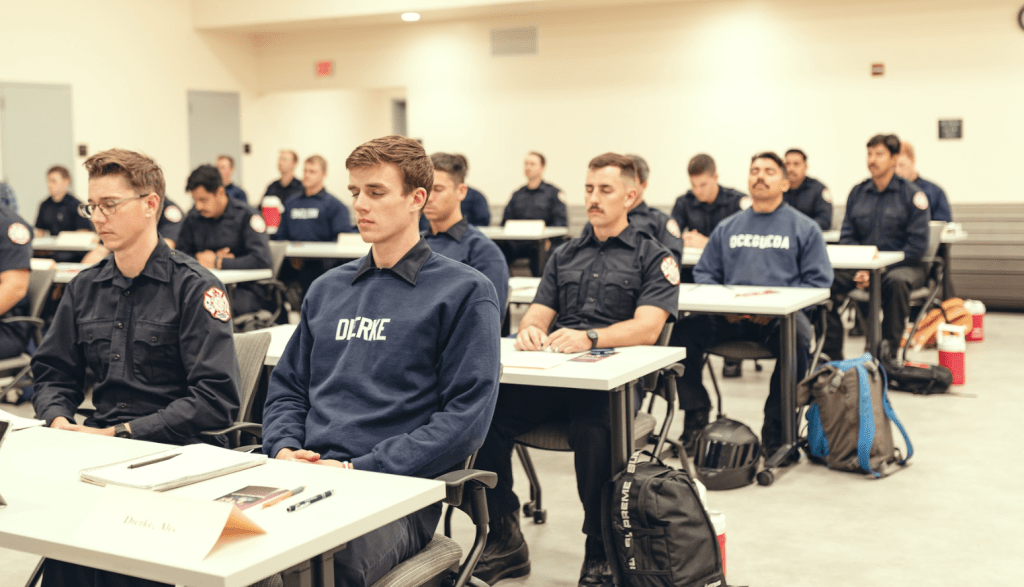

He sat quietly, respectfully and perhaps a bit nervously—not unlike the others in attendance. He was one of 50 mostly male first responders at Bishop’s Ranch event center in Healdsburg in early November 2025 attending the opening of a three-day training workshop put on by First Responders Resiliency, Inc., the Sonoma County nonprofit dedicated to “Putting PTSD Out of Business.”

“Some of you probably think you don’t need this [type of training],” predicted the nonprofit’s founder and director Susan Farren, a former paramedic and paramedics supervisor, in her opening presentation to the attendees. “But I guarantee either you do, or you know someone who does.”

Attendees are invited to use a variety of tools on the tables before them— pipe cleaners, stress balls, coloring pages—common objects scientifically shown to help release stress while learning, and activating a part of the brain stimulating recovery and focus.

In broad terms, the trainings address stress—understanding it scientifically, recognizing it physiologically and alleviating it personally.

But these aren’t your typical find-your-spirit-animal meditation retreats held throughout the North Bay for decades. This is for people whose job is to fix bad situations asap—a family’s house is burning, someone’s spouse is violent, Grandpa is in cardiac arrest. First responders often play a prominent role in someone’s worst day, making immediate, informed and potentially life-altering decisions, driven into action by the body’s instinctual fight-or-flight response. Over time and with enough constancy, the body adopts fight-or-flight more permanently, taking an incredible toll on the body. However much they try, first responders can’t simply “leave it at the office.”

Not every distress call is earth shattering; not every day is haunting. But if each trauma is like a small stone collected in a backpack of first-responder stress, over time the weight will bear a heavy burden—one that can carry a steep cost.

Retired Oakland firefighter Michael Donner’s “backpack” is loaded with stones from a more than 30-year career that found him responding to such emergencies as the Loma Prieta earthquake, Ground Zero on 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina. He’s attended each of the nonprofit’s trainings since 2024, when the weight of his backpack became too much and he suffered a near-suicidal breakdown that drove his fiancé to the brink of leaving him. Through the trainings he’s gained understanding how his career has affected him physiologically and how certain daily routines can reset his nervous system. “I bought into the program,” he says. “And it has changed my life.”

A few facts: First responders are demonstrated to have higher rates of alcoholism than the general population, with studies showing 58% of public-safety professionals binge drinking within the past month. Another study by The First Responders Initiative found between 60-75% of first responders’ first marriages end in divorce. Most alarming, emergency responders are 1.39 times more likely to die by suicide, according to 2024 statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

First Responders Resiliency trainings carry the promise that participants will come away with tools and techniques to navigate the stress and mitigate the toll on physical and mental health brought by a career whose primary responsibility is to wade knee-deep into other people’s most traumatic moments.

The goal, the nonprofit’s website contends, is if the trainings serve their purpose, they “may save your life.” The mission, it continues, is to “Put PTSD Out of Business.”

And the vision: To take this culture-changing model of physiological- and mental-health awareness global.

The girl who lived

Susan Farren is supposed to be dead. The Sonoma Valley native had spent her decades-long career in emergency services—first an EMT, then paramedic and later a trainer and supervisor—working throughout the Bay Area, raising five kids with her firefighter husband of 23 years. After a long, hard-worked career she’d retire and settle into an easier life—that was the idea, circa 2015, at least. But as emergency personnel know better than most, the best-laid plans oft go awry.

Despite hopes that she’d graduate from her career “unscathed,” as she puts it, Farren wasn’t immune to the purgatories often faced by first responders. First came an “unwanted” divorce. That devastating dissolution led to her losing healthcare coverage—which, in turn, necessitated a return to work.

With the end of her marriage forcing her out of retirement in 2016, Farren had been at a new job in Oakland for less than five months when, as she puts it bluntly, “I began to urinate blood.” Twenty-four hours and multiple oncology body scans later, Farren’s doctors delivered grave news: They found a tumor on her right kidney, and a mass on her liver they believed had metastasized from her chest. They said she had a year to live. She was 51, with five kids between ages 12 and 19 and a divorce just finalized.

Her medical team began arranging her placement to hospice care.

And that’s where Farren’s story begins.

Because, as Farren likes to remind people taken aback by her run of bad fate a decade ago: “Don’t worry—I didn’t die.”

A follow up scan would be her “stay of execution,” as she calls it. The mass on her liver was revealed to be a hemangioma—a birthmark. Cancer had not spread; the tumor was isolated to her kidney and could be removed surgically. She could take her list of palliative services off speed dial. A full recovery was expected.

And it was in the days following surgery to remove the kidney tumor that Farren heard the cast-off comment from a physician that would redirect her life. “We see a lot of this in first responders,” a doctor said.

“See a lot of what?” she responded.

“Organ cancers.”

Born under punches

When Farren returned home to recuperate from her cancer surgery, she was still haunted by what the physician had said. “And the first thing I did was google: organ cancer first responders,” she says. She immediately found articles in medical journals focused on the correlation between first responders and organ cancer, specifically around the constant accumulation of adrenaline and cortisol, a primary “stress hormone,” in their systems. Her research led beyond organ cancer to other maladies plaguing first responders—strokes, heart attacks, divorce, addiction, suicide. She came to a sobering realization: “The work we did was actually killing us.”

The numbers don’t lie. First responders are statistically more likely than the general population to develop a litany of diseases—skin cancer, mesothelioma, Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, kidney cancer and Lou Gehrig’s disease among them. Female firefighters are observed to develop breast cancer at six times the rate of the rest of the female population. Firefighters overall are at a 1.21 times greater risk of colon cancer; a 1.58 times increased risk of mesothelioma (a cancer in the lining of internal organs, usually caused by asbestos exposure); and at 1.53 times greater risk of multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer.

[Will Bucquoy Photography]

The risks are cumulative, increasing the longer one stays on the job. And while occupational exposure to toxic chemicals and other substances play their part—especially in the fire service—lifestyle factors among first responders are major contributors to negative health outcomes. Substance abuse, sleep irregularity, divorce, depression and anxiety top the list of issues leading emergency personnel to chronic disease. Equally alarming: Recent studies describe the suicide rate among first responders as “the silent crisis,” far exceeding rates in the general population, with police and firefighters more likely to die by suicide than in the line of duty, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. In 2024 alone, 133 first responders died by suicide in the U.S., according to research from the Firefighters Behavioral Health Alliance—and it is estimated around 40% of cases go unreported, meaning the actual numbers are significantly higher. Over this past Thanksgiving weekend, a Berkeley fire captain hanged himself, three weeks before retirement.

None of this was a surprise to Farren, who estimates throughout her career she’s known more than a dozen close colleagues take their own life. Farren herself, gripped by depression following her cancer and divorce, harbored serious thoughts of suicide. It was following one severe mental health episode, which resulted in a four-month stint in an intensive outpatient program through Kaiser Permanente, when Farren had an epiphany.

Playing on the adage that necessity is the mother of invention, Farren prefers a slight variation: Adversity is the mother of invention. “And out of that adversity I was given a vision to build a center for first responders to help them have a healing space that I could not find in my darkest moment.”

After more than 30 years in emergency services, Farren found her second calling: Helping those who save others, to save themselves.

With the consent of her children, Farren sold their family home for the seed money to launch First Responders Resiliency, Inc.

She started small—a short presentation in September of 2017 on trauma and stress to the Sonoma Valley fire department staff. Then, three weeks after closing escrow on her home, the Tubbs Fire erupted, scorching tens of thousands of acres throughout Sonoma, Napa and Lake counties—more than 10,000 first responders from 17 states helped beat back the flames, which burned more than 5,600 structures and claimed 22 lives. By the time the fire was contained on Oct. 31, Farren was more determined than ever to realize her vision.

By June of 2018, the nascent nonprofit held its first training for 40 attendees at Westerbeke Ranch in Sonoma.

A grand vision

Today, seven years since its debut at Westerbeke, First Responders Resiliency has become a team of more than 20 volunteers and staff run by career first responders—paramedics, police officers, firefighters, an emergency physician and former military special forces—and has held more than 230 trainings attended by more than 12,000 emergency personnel and their families (including two multi-year contracts with Cal Fire, as well as federal law enforcement in Washington, D.C.) The nonprofit’s tagline is: Putting PTSD Out of Business. While post-traumatic stress hasn’t filed for bankruptcy just yet, those kinds of event and attendance numbers mean it’s certainly on notice.

And there’s a logic to their work: If stress is the No. 1 contributing factor to disease, and research shows it is, then it seems right that reducing stress is the No. 1 contributing factor to reducing disease.

But confronting stress and trauma in emergency personnel who may be decades into their careers isn’t the endgame, emphasizes Farren. Equal effort must be put into educating those entering the industry. The “grand vision,” she says, is to change the culture for first responders—worldwide. “Never again do we allow them to go into the industry without them knowing the physiological effects of stress on and trauma on the human body.”

Farren foresees resiliency training becoming a requirement for everyone entering the emergency response industry—so rookies come in eyes wide open about how their brains, bodies and nervous system will be affected by the work.

Importantly, the information is backed by science-driven data, with the nonprofit working with such researchers as Dr. Torey Van Dyke at Loma Linda University, Dr. Gina Poe, director of brain research at UCLA, and neuroscientist Dr. Ryan D’arcy to provide cutting-edge technology to the first responder community.

Importantly, the information is backed by science-driven data, with the nonprofit working with such researchers as Dr. Torey Van Dyke at Loma Linda University, Dr. Gina Poe, director of brain research at UCLA, and neuroscientist Dr. Ryan D’arcy to provide cutting-edge technology to the first responder community.

The centerpiece of the “grand vision” is an 18-acre parcel near Cotati that was once home to the Washoe Creek Golf Course. On former sand traps and putting greens will be the First Responders Resiliency Center, a self-care sanctuary for first responders and their families. The first of its kind, the center will be a wellness center offering myriad services available on a drop-in basis (including a long-awaited training center for conferences)—plus culturally competent therapists, a wellness program, resources and support for drug and alcohol addiction, an equine center, as well as a cancer research center dedicated to studying health afflictions specific to first responders. The program will stay on the cutting edge of techniques that can support clients’ nervous systems and health including art therapy, massage, cold plunges— anything that helps get the first responder physiologically out of fight or flight, says Farren. “This will be the mother ship of resiliency centers in the world.”

The nonprofit purchased the land in 2021, after being outbid by multiple would-be buyers. (According to Farren, the property owner felt it was a moral imperative to sell to the First Responders Resiliency cause—and even covered the closing costs and co-signed the loan for the purchase.)

The proposed First Responders Resiliency Center project is currently under review by the county’s planning department, Permit Sonoma. “If we can get the permits, we’ll break ground,” says Farren. Construction will be done in three phases. First the classrooms and rooms for research and other core services. Second, the self-care sanctuary. And, finally, administrative offices. (In typical first-responder fashion, Farren and her team’s space comes last.)

Key to realizing the project will be reaching their fundraising goal of $3 million, which will make them eligible for the full construction loan. Farren says some interested donors are taking a wait-and-see approach before cutting a check. “When a woman comes out of nowhere, with five children and an idea—it’s easy to step back and say, let’s see if she can maintain this,” says Farren. “And I do, with an incredible team of first responder instructors and volunteers beside me. It’s not something we’re doing for fun, we’re doing this because our partners were dying prematurely or taking their own lives.”

Adds Farren: “We mean business.”

‘You are not alone’

Back at Bishop’s Ranch, the third and final day of training is “family day.” Spouses, partners, kids over 14 and various significant others gather in an area separate from their first-responder loved ones and are given an abbreviated 8-hour course of what’s been presented at the training that weekend.

This is the time for families to better understand what’s happening physiologically as a result of their loved ones’ careers. And, reminds Farren, it’s a chance for families to understand what they can be doing to care for themselves during the process.

By this time, the pages have been colored, the pipe cleaners bent into all sorts of shapes and knots. Membership in the F- Your Feelings Generation has dropped to nil. After three days of lectures, modalities, yoga (taught by a military veteran), breathwork, meditation and other stress-mitigation techniques, it’s time for home. At that point, the families reunite with attendees—and many feel like, for the first time, they both understand what’s happening, says Farren.

Carie Levar was so impacted by family day when her firefighter husband attended a 2019 training, she became the nonprofit’s director of Family Services.

“You can watch the metamorphosis—letting down that guard, getting down [from] fight or flight.”

Levar describes the relief first responders feel as being like, “when you finally know somebody gets it—you are not alone.”

Donner, the Oakland firefighter, recalls family day at his first training weekend in 2024. His engagement was crumbling following a breakdown—his fiancé was ready to leave him, when she agreed to attend the family day. “I’ll never forget this,” he says. “She drove home with me, and when we got in the car she started crying. And she said, ‘I had no idea—you have every symptom they were describing.’”

Adds Donner: “At the end of the day we are ordinary men and women doing extraordinary work, for decades. How could it not affect us?”

A year later, Donner and his fiancé are still together. “We are closer now than we have ever been.”

For information on First Responders Resiliency, Inc., including trainings, resources, family services and how to join the capital campaign to build the world’s first Resiliency Center for first responders, visit resiliency1st.org.

Raven Drum Foundation bangs the drum for first responders

Rick Allen is a legend in music circles. The Def Leppard drummer famously came back from a 1984 car crash that resulted in the loss of his left arm. With the support of his bandmates and drum technicians who designed a specialized kit for the Dronfield, England native, Allen is still pounding the sticks for Def Leppard to this day. In 2001, he and spouse Lauren Monroe founded the Raven Drum Foundation, a nonprofit supporting veterans and first responders by hosting drum circles and other healing events which provide skills and methods to navigate physical and emotional symptoms of trauma, anxiety, pain and isolation. Raven Drum is one of First Responders Resiliency’s biggest supporters, partnering with the Sonoma County nonprofit for events, fundraising and to raise awareness and build techniques for mitigating stress, anxiety and the health effects of trauma. Visit ravendrumfoundation.org.